Reclaiming the Body: Photography and Feminism with Ponch Hawkes

Renowned for capturing the raw beauty of the female body, LGBTQI+ activism, and inter-generational relationships, Ponch Hawkes is an Australian photographer who set the scene for the Australian feminist art moment.

Vertigo had the opportunity to chat with Ponch about the historical influences guiding her photography, the emotional resonance of her projects, and her journey to where she is today.

Images provided by Ponch Hawkes

V: Hi Ponch, thank you for taking the time to chat with us. Could you begin by introducing yourself to our Vertigo readers?

PH: I’m a photographer who lives and works in Melbourne on the land of the Wurundjeri. I used to be a librarian and was a journalist for an alternative paper, but I’ve basically earned my living by being a full-time photographer and artist since 1988.

V: What inspired the career change to full-time photography?

PH: There’s nothing quite like the thrill of photography. I found a camera in the cupboard where I was working, had it repaired, and I just started taking photos. As I was on a publication, my photographs got published, which was very encouraging. This was also when there were hardly any women taking photos, and the other women who needed photography commissioned me to do work, for which I was not really able to do, but which meant I took a risk and learned how to do it.

V: Your photography has been an influential part of the Australian feminist art movement. How do you use photography to engage with social issues?

PH: I don’t know any other way to do it really. The issues which my work is about, are the issues that interest me as a person. They’re about my politics, so that’s where the photography comes from. I just follow what I’m thinking about, what I’m talking about, and what I’m trying to investigate.

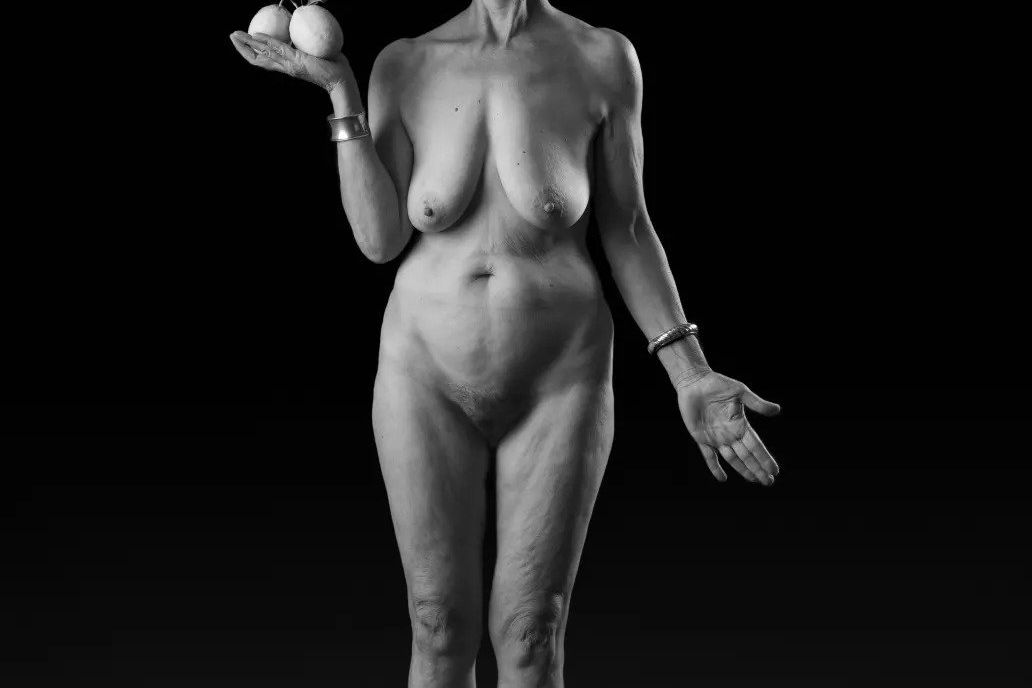

V: A sustained theme throughout your work is the focus on bodies. How do you use the framing of bodies to empower individuals, and what role does the nude body have in art?

PH: The nude body has had a place in art since people started drawing on cave walls.

What has been missing is anybody other than younger women, which, although very beautiful, has meant that we’ve had a very gendered view of ageing and how the human body changes throughout its lifetime.

Older women are completely invisible in the nude pantheon. Really, my work with the bodies is dance and theatre and circus and a whole range of activities where people use their bodies. I just love being engaged with that, and I’m a huge sports nut, so I love the way people engage with their bodies in sports. I’d like to think I have a feminist perspective on it, and that’s how I approach photography.

V: 500 Strong is a fantastic representation of the female body. Can you tell us about the concept behind the project and the reception it received?

PH: It was a commission for a show called Flesh After Fifty: Changing Images of Older Women in Art, which commissioned about 15 artists to make representations of older women. Professor Martha Hickey, from the Royal Women’s Hospital, discovered that women who reach menopause early, often thought their lives were over and that there was nothing left for them. Struggling to find a medical way, Martha was trying to find a way to show women the range of activities and ways you can talk about ageing.

Jane Scott was a curator, and she commissioned me for this large-scale project, and it was fantastic! Women were very brave to show up and take their clothes off in front of something they didn’t know, even if they were feeling shy or maybe even ashamed, and just to be so… bold, is what I want to say, that’s what was so exhilarating.

I think this project was so powerful because it’s the first project that I would really say whose aim was to make social change. It was apparent from people’s responses, especially older women, that they were affected by seeing that the way their bodies looked was normal.

Ponch Hawkes, 500 Strong (2019-20)

Ponch Hawkes, 500 Strong (2019-20)

Ponch Hawkes, 500 Strong (2019-20)

V: What emotions do you want your photographs to evoke from viewers?

PH: It depends on what it is, how I’ve approached it, what the subject is, and what the context is. As I mentioned before about 500 Strong, the response to that project has been so strong and emotional about how incredible it is that a piece of work has changed their lives by participating in it or seeing it.

Of course, photography has emotional resonance for various people in various instances, and people can easily misinterpret what you do, but you can’t do anything about that. All you can do is make it laid out and try to make it sit in the context.

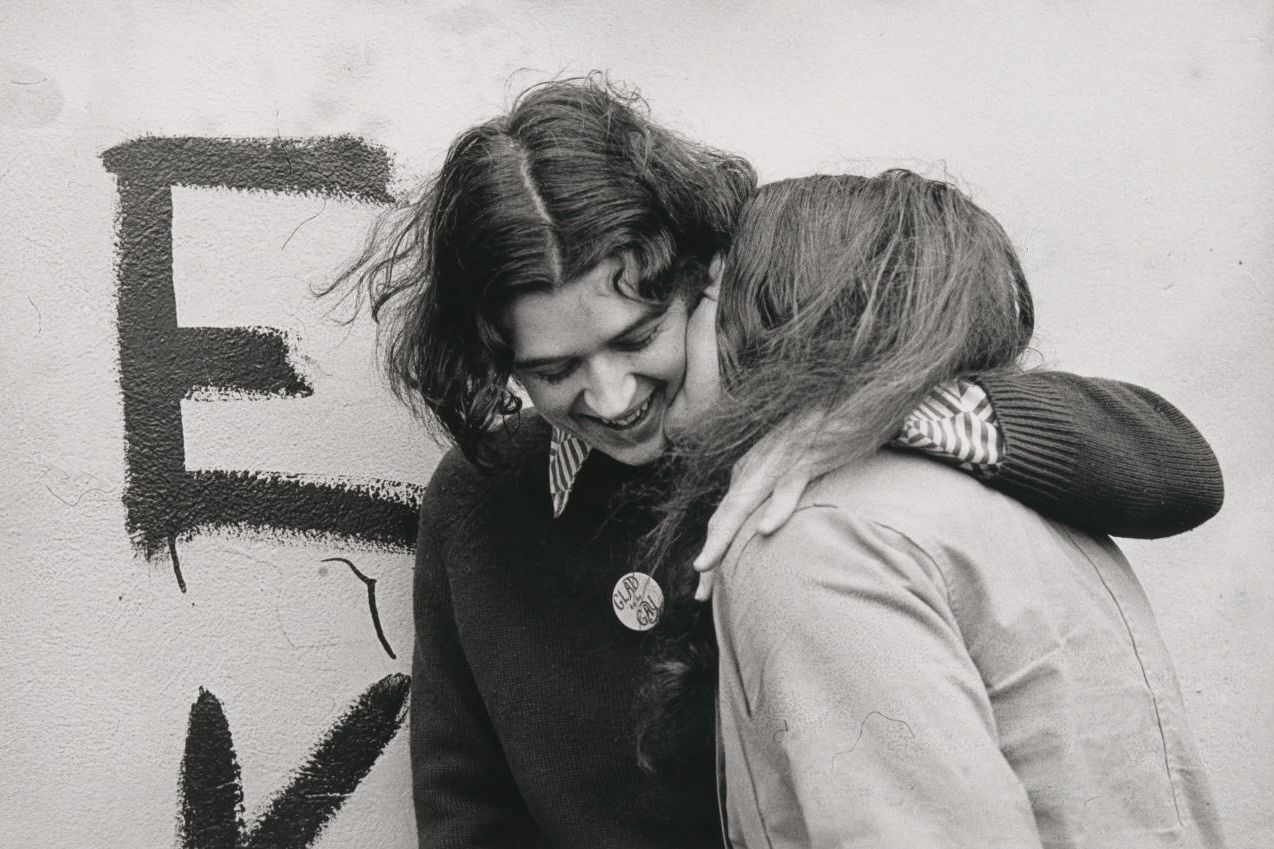

V: Your 1973 photograph, No title (Two women embracing, ‘Glad to be gay’), is featured in QUEER: Stories from the NGV Collection. What is the backstory behind this image, and what is your relationship with queer stories and photography?

PH: It’s hard to imagine now, but I had been focusing on one or two gay liberation marches that had taken place in Sydney, and Melbourne, a group of women had started a lesbian group from my peer group. It was such an exciting time in the early ‘70s in Melbourne — feminism had largely come to us from the States and the UK — and we felt like we were going to say things, and the entire world was going to listen and change. Women were setting up all types of groups, and those women in the photographs, Jenny and Sue, were in one of the groups I moved around with.

V: What has been the most enjoyable experience during your career?

PH: The new is one thing.

I love to explore new things, and one of the things that photography does is give you an incredible entrée.

People can also be very trusting, so they give you an incredible look into their lives which is a great privilege and enables you to make really interesting work.

It’s also true that my work is very collaborative. If I’m taking photos of somebody or a group, they’re usually involved in discussion beforehand about what the outcomes might be. That’s a part of my view of photography; I like to engage with the people I’m working with.

V: What art piece or project has meant the most to you?

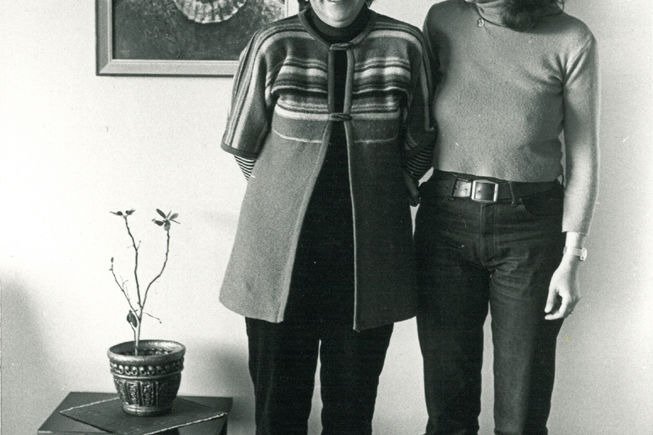

PH: It’s like choosing a baby, not that I have any babies, so it’s more like choosing one of my dogs (laughs). Every decade there is probably one or two, like the very first project I did is the one that I’m most well-known for, which is Our moms and us. They say that as an artist, you only have three ideas, and that’s one of mine as it’s a particular work that the National Gallery of Australia collected. But you know, your latest work is your favourite as well, so it’s kind of what you’re working on now that will always be the one you’re in love with.

V: How do you think the photography landscape has changed since the beginning of your photography career?

PH: Personally, it’s changed a lot. I used to see myself as a photojournalist, which is what I did, and then later, I probably started to think about myself as a documentary photographer. Now, I would definitely call myself a photographic artist as my work started to change to make constructive imagery and be more adventurous.

V: What advice do you have for young photographers trying to find their distinct style?

PH: My advice would be to do what you’re interested in and be really nice to everybody because you don’t know where you’re going to meet them on the way up or down. The art world in Australia is very small; don’t fall out with people. The people you know now at university or whatever group you’re in are going to be people you know for the rest of your life, so be gentle with them.

There’s also plenty of people with talent, so you can’t get away without working hard. You can have a bit of luck, but you don’t get too much luck in this business. You really need to put your head down and commit to projects, and you have to be prepared to be poor. You have to be prepared to invest in your career. You have to be prepared to pay that $30 for a competition because important people will judge and see your work, and even if they don’t accept you as a finalist, they might remember your work.

V: What ideas are you working on now, and what does the future look like?

PH: The future looks pretty busy, actually. My show is currently at Geelong Gallery, and then will be going to Shepparton Art Museum and Horsham Regional Art Gallery. I’m currently engaged in a body library, which is half-way done now. I’m also working on a personal project collecting X- rays. I don’t exactly know how to use them yet, but I’m in my experimental stage.

If you’re looking for more work by Ponch Hawkes, check out her website here!

Ponch Hawkes, No title (Two women embracing, ‘Glad to be gay’) (1973)

Ponch Hawkes, No title (Women’s liberation demonstration in City Square) (1975)

V: What has been the most enjoyable experience during your career?

PH: The new is one thing.

I love to explore new things, and one of the things that photography does is give you an incredible entrée.

People can also be very trusting, so they give you an incredible look into their lives which is a great privilege and enables you to make really interesting work.

It’s also true that my work is very collaborative. If I’m taking photos of somebody or a group, they’re usually involved in discussion beforehand about what the outcomes might be. That’s a part of my view of photography; I like to engage with the people I’m working with.

V: What art piece or project has meant the most to you?

PH: It’s like choosing a baby, not that I have any babies, so it’s more like choosing one of my dogs (laughs). Every decade there is probably one or two, like the very first project I did is the one that I’m most well-known for, which is Our moms and us. They say that as an artist, you only have three ideas, and that’s one of mine as it’s a particular work that the National Gallery of Australia collected. But you know, your latest work is your favourite as well, so it’s kind of what you’re working on now that will always be the one you’re in love with.

Ponch Hawkes, Mimi and Dany (1976) from the series Our mums and us

V: How do you think the photography landscape has changed since the beginning of your photography career?

PH: Personally, it’s changed a lot. I used to see myself as a photojournalist, which is what I did, and then later, I probably started to think about myself as a documentary photographer. Now, I would definitely call myself a photographic artist as my work started to change to make constructive imagery and be more adventurous.

V: What advice do you have for young photographers trying to find their distinct style?

PH: My advice would be to do what you’re interested in and be really nice to everybody because you don’t know where you’re going to meet them on the way up or down. The art world in Australia is very small; don’t fall out with people. The people you know now at university or whatever group you’re in are going to be people you know for the rest of your life, so be gentle with them.

There’s also plenty of people with talent, so you can’t get away without working hard. You can have a bit of luck, but you don’t get too much luck in this business. You really need to put your head down and commit to projects, and you have to be prepared to be poor. You have to be prepared to invest in your career. You have to be prepared to pay that $30 for a competition because important people will judge and see your work, and even if they don’t accept you as a finalist, they might remember your work.

V: What ideas are you working on now, and what does the future look like?

PH: The future looks pretty busy, actually. My show is currently at Geelong Gallery, and then will be going to Shepparton Art Museum and Horsham Regional Art Gallery. I’m currently engaged in a body library, which is half-way done now. I’m also working on a personal project collecting X- rays. I don’t exactly know how to use them yet, but I’m in my experimental stage.

If you’re looking for more work by Ponch Hawkes, check out her website:

-

-