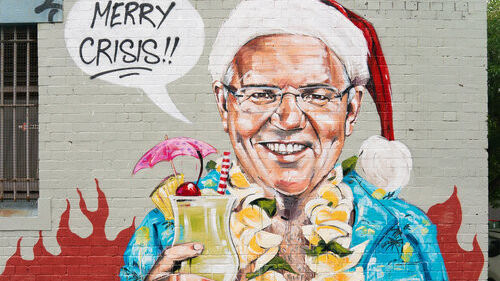

Merry Crisis: In Conversation with Scott Marsh

When Scott Marsh’s mural of Kanye West passionately kissing himself appeared on a Chippendale street in 2016, no one could have anticipated the wide-spread recognition that would follow. Within weeks, the image was circulating news media landscapes all over the world, and members of the public were cueing up to take photos. In the years since, Marsh has acquired the type of reputation most street artists could only dream of, not least of all for his caricatures of conservative Australian MPs.

For this issue, Vertigo sat down with the Sydney-based artist to discuss the origin of his practice, and the place of art in political discourse.

All photos from scottmarsh.com.au

V: How did you get engaged in the Sydney art scene?

SM: Since I was twelve years old, I’ve been writing graffiti — tagging and all that stuff — and that kind of took over my life. I became obsessed with it all the way through my teens and into my twenties. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve built up this skill set that I’ve acquired through graffiti. I’ve learnt how to use spray-paint, learnt how to paint outside, learnt how to draw, whatever. I studied Fine Arts at the University of New South Wales and started using those skills to paint little commissions for cafes and stuff. Eventually, I started painting murals and found a political voice through that. I think the hardest part for any artist is not really figuring out how to paint, but figuring out what you want to paint and what you want to say. I was fortunate to find that.

V: Was there an “ah-hah!” moment when you figured out what you want to do?

SM: Yeah, well, I wasn’t politically engaged at all as a teenager or as an artist in the early days. It was actually the lockout laws that got me politically engaged. I lived in Kings Cross while I went to university and a lot of my friends were bartenders or DJs. I basically watched Kings Cross die. It still hasn’t recovered from those lockout laws. I painted a ‘Casino Mike’ mural, which was a mural about Mike Baird as he was leaving the casinos open while everything else had to close. That got a lot of attention, and I was receiving a lot of media requests about it; I was like, “Fuck. I better research this guy so that I don’t look like a fucking dickhead”.

When I looked into it, I realised there were a bunch of his policies I didn’t agree with.. I started looking at other people’s policies more broadly and it just started from there. It gave me an outlet for wanting to say something that was serious, but at the same time, I’ve always been a bit of a class clown character, so it gave me an opportunity to be funny and goof around as well.

V: You said earlier that you’ve been graffitiing since you were twelve. Did you grow up in a particularly nurturing art scene?

SC: Well, I grew up in a graffiti scene, and that was just fighting and graffiti-writing — it definitely wasn’t nurturing (laughs).

There were a bunch of us who would all paint graffiti together, some very talented guys, and we’ve all kind of gradually made the transition into art as we’ve gotten a little bit older and needed to make a living. We had these skills, but all we wanted to do was paint graffiti, so we started painting murals, and we’ve all become reasonably successful. That was the kind of community I had. It wasn’t an arts community; it was a graffiti community.

V: There are a lot of in-studio prints for sale on your website —was it difficult moving from a graffiti background into a fine arts practice?

SM: Yeah, I often get asked, “How was it learning to paint outside?”, whereas it was the opposite for me. I’ve always been painting outside since I was about twelve, so it’s perfectly normal for me to be painting massively on a wall. It was building a studio practice and trying to translate what I was doing — making it smaller and fitting it onto a little canvas — that was the hardest thing, because you have to invent yourself in a different way and reappropriate all the skills.

V: Is there a practice you prefer more?

SM: Nah, they’re just different. The process of painting in the studio is a lot more experimental. You paint something, then have a look and change it — you play around a lot more. When you’re painting a mural, just because of the scale, you’re making a plan and then executing it. You don’t really have time to stand back and go, “Oh, I might add a little bit of this or a little bit of that”. You have to figure all that out before you start painting.

Even now, in terms of the art scene, I’m an outsider. I come from a graffiti world; I’m not from a fine art world. I don’t exhibit in commercial galleries.

V: You said a little while ago that you did a Bachelor of Fine Art, but you’ve also completed a Bachelor of Education. Have those come in handy for you?

SM: When I studied art, I was shit — I didn’t pay attention or absorb any of it. When I went back to study teaching, I had to revisit all that art history stuff, and it’s important to see what other artists have done before you, because that informs your practice. That part of it I found really helpful.

V: Were there any standout artists that inspired you?

SM: When I was in high school I loved the work of Honoré Daumier. He was a French political artist from the 1800’s who drew satirical cartoons. I based my major work in the HSC around one of his paintings. I loved his work, but I never read what it was about because I didn’t care; I just liked the aesthetic. Later, when I went back to teaching, I had to write some essays so I decided I may as well write an essay on Honoré Daumier. When I looked into it, I found that he was actually painting about politics and doing exactly what I’m doing now, but way back in the day. He even got arrested a bunch of times for painting cartoons about the French king, so he was pretty gangster. But it was just interesting that I was attracted to his work but had absolutely no idea what it was about.

V: How important do you think art is in political discourse?

SM: In a free society, you’ve got to be able to take the piss out of your politicians and your leaders, and they’ve got to have the skin to cop it. In that sense, I think it’s important. It’s also just part of the Australian identity — that larrikin nature of taking the piss out of yourself and your mates. I love that part of it, and I think it’s a little bit of an extension of that.

V: There’s a great level of variety to the street art that you do. You’ve got everything from the ‘Bill Shorten as Two Face’ piece to the Tony Abbott caricature: ‘100% C**t’, which isn’t as thoughtful as it is just empathetic about people’s hate towards Tony Abbott as a politician. When you make these artworks, do you consider the specific impact you want to have: who’s going to see it and what you want them to be thinking?

SM: A lot of it is exactly like that — I’m always thinking about the audience. When you paint in a public space, you’ve got to figure out who’s going to see it, and if you’re trying to say something, you’ve got to figure out who you’re saying it to, and how to craft a message that’s going to get through to them.

The best tool is humour. Humour cuts through all the bullshit.

The hardest part for me is finding walls. Location can add so much conceptually to the piece. If I can paint that Tony Abbott mural in his electorate or near his office, it’s a lot more fun. The politicians can never get those walls. With those paste-up murals specifically, I can play around with location a lot better.

V: How important is audience interaction to you?

SM: The first time I noticed it was when I painted the ‘Kanye Kissing Kanye’ mural which went really viral, and there were lines of people queuing up to take selfies in front of it. Getting people to interact with art in a public space that’s not a gallery or institution is fun. I did the ‘Fraser Anning Easter Egg Hunt’ where people would chuck eggs at a mural of Fraser Anning’s head. There’s another one with Clive Palmer; he used to fall asleep in Question Time when he was in Parliament, so I did ‘Draw Dicks on Clive Palmer While He’s Sleeping’ by leaving some Sharpies on the wall underneath posters of him sleeping.

I’m always trying to think of ways to get the audience to interact with the work. It’s fun for me, and it’s fun for the audience. Galleries and institutions are awesome, but it’s really hard for normal people to step inside them because they’re an intimidating space. If you can frame stuff in a public space, in a normal environment where they’re comfortable and can interact with it, it gets people engaged in art.

V: Of course, the flipside of that is when people try to censor your work, as happened with the ‘Tony Marries Tony’ mural. Does that bother you?

SM: Yeah, I’d prefer it didn’t happen, but that’s just part of painting in a public space. It happens more and more these days, and disturbingly it happens more and more from the left. People get on their woke high-horse and have problems with just about everything. Rather than letting it be, they want to cancel it, which kind of sucks, but it is what it is.

V: Do you ever miss being an unknown street artist?

SM: Nah, I’ve never attached my face or identity to my work, outside of just “Scott Marsh”, so I feel like I’ve kept a little bit of my anonymity. If I ever want to paint something that’s not under my name. I can just go do that (laughs).

V: If you were talking to a younger artist who found themselves in the same position that you were, what advice would you give them?

SM: The most important thing is just to do what you want to do. Don’t do what you think is going to make you successful, and don’t do what you think people are going to like. Find your voice and do exactly what you want to do. For me, the moment I stopped think - ing about what was popular and how I would sell a painting was the moment I became successful. Don’t listen to all the other bullshit.

-

-