Natasha Hertanto, author of 'The Blue Hole'. (Photo provided by Natasha)

Natasha Hertanto arrives an hour early to our Zoom interview, which sets the tone for the next hour: slightly chaotic and a little unfocussed. We go off countless tangents, from voyeurism in China, to Bahasa class in high school, to Bali beaches vs. Melbourne beaches.

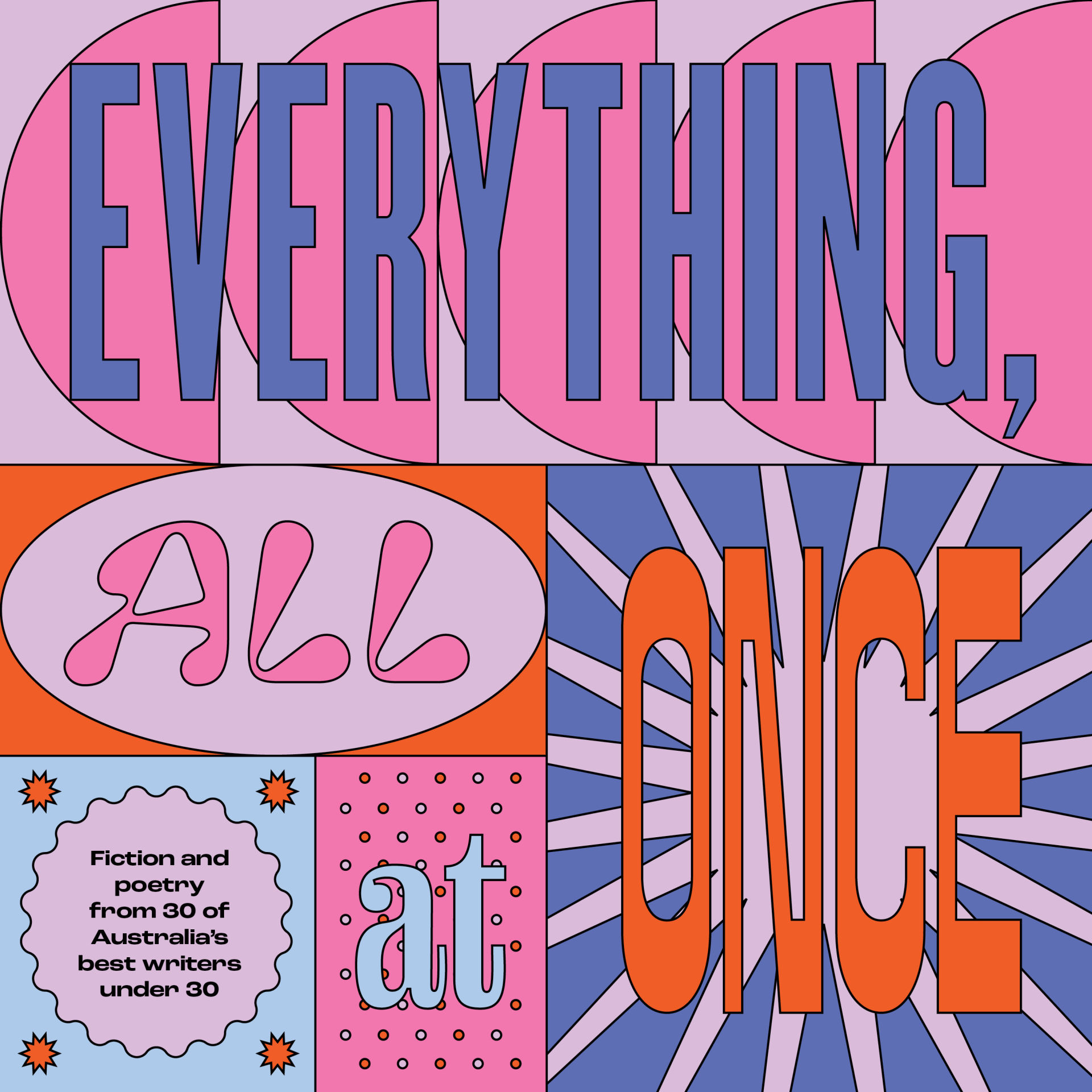

Natasha is a Naarm-based Chinese-Indonesian writer who dabbles in fiction, nonfiction and occasionally poetry. Her short story 'The Blue Hole' is featured in Everything All At Once (Ultimo Press), an anthology of work by emerging writers under 30. 'The Blue Hole', a fantastical story, features a unassuming GoPro — found at the bottom of the ocean — that takes the protagonist on a journey of love, grief, and identity.

Angela: There was an actual expedition that explored the Great Blue Hole and bodies really were discovered at the bottom. What was it about that news story that inspired you to extrapolate and retell it creatively?

Natasha: I was in the car with my partner and he put on this podcast. It was such an intriguing setting. It was so strange and haunting. Of course there are random holes at the bottom of the ocean — why wouldn't there be? But most people don't know about it. And I just kept thinking, what kind of person would be interested in going on this expedition? What would motivate them to do something like this?

I did quite a bit of research before writing. It takes a lot of training — months and sometimes years depending on the depth that you're aiming for. You have to go in with a team of professionals, and you do mental strength training, physical strength training because it's freezing down there and it's pitch black. You can't even see your hands in front of you. So, I thought about whether there was a time in my life where I felt that way, without being there physically. And I just thought about when my grandpa passed away, and when my dog passed away. The first time you get your heart broken, and the second and third time. So, when [the podcast] mentioned finding a GoPro, everything just kind of clicked: imagine finding this GoPro and it has a movie about your life or movie about someone that you miss.

Angela: Which is fortunate for the protagonist; it allows her to revisit memories of her and Mei. How do you feel about how we constantly capture moments on camera, even for the most mundane moments?

Natasha: I'm really guilty of this. I think most writers and artists have an obsession with archiving their life. But I don't know — does it come from a good place if you want to be able to look back and see that you've done okay with your life? But from a social media standpoint, is it just vanity?

And what is mundane? Because since COVID, obviously we have less things to show the world; we're just in lockdown. People's pictures have changed from meeting friends at the bar to ‘Here's this cool cake that I made in the last three hours!’ So, I guess if it showcases what brings you joy, and some aspect of your personality, maybe it's okay?

Angela: But I do feel like there is a line and that line is if it borders on obsession. Did you find 'The Blue Hole' an easy story to write?

Natasha: [It was] maybe emotionally exhausting, because it has a heavier undertone. I wrote it in two nights actually. I was rushing to meet the deadline to enter the anthology. It was so fast, but it's more common for me to think about the story a lot first, and play out the dialogues and the lines in my brain for weeks. And so when I sit down, I can just go *rapid typing noises*, because I already know what I want to say. It's just my working style.

Normally when I write stories, I don't really have 'a target audience'. Sometimes writers say, ‘Oh, you have to think about who it is you're writing for, blah, blah, blah.’ If it was freelance work, then maybe; but with stories, normally I just do whatever I want.

But with this [story], I had a very specific type of reader in mind. They have to be willing to put in the work, to read it multiple times and catch all the Easter eggs.

I think if you [only] read at once, you're not going to catch all of them. For example, even though the protagonist is nameless, Mei mentions her gender as female, but most people didn't catch that — and the people who didn't are usually hetero. They kept referring to the protagonist as a ‘he’. Because Mei is a girl, they kept thinking, ‘Oh, you're writing as a guy!’ And I was like, ‘...If you read it closely... you will know that's not true!’ That's what I mean by having a sharp reader.

Angela: A big part of Vertigo is showcasing local talent, young talent, diverse talent. When I first came across your story, the first thing I saw were Chinese characters. And anyone who blends Asian languages into their English prose — I want to talk to that person! I love how you subtly sprinkled Bahasa Indonesia and Mandarin into your story. Do you often feature other languages in your work? And what kind of effect do you think that has on your storytelling?

Natasha: Well, full disclaimer, I can only speak Bahasa, and at this stage, not very fluently. I migrated seven years ago and a majority of my friends who do speak [Bahasa] have either gone home, or they've moved to a different country. My family mostly speaks English as well, so there's just not a lot of people I can use the language with. And over the course of a few years, you just very slowly start to not know what you don't know. Until you have to talk with [a native speaker], and then you're just like, 'What are pronouns? What is grammar?'

Angela: And they always speak so fast!

Natasha: I know! I was trying to order this bouquet for my sister a few weeks ago [through WhatsApp]. It's all in Bahasa, and I took so long to reply — I must have sounded like a really stiff robot. I think [the lady] saw that my number wasn't an Indo number and she switched to English because she felt so bad for me. And it made me so sad! I think that's a large part of why I tried to include Bahasa, because I don't want to forget it. And it's just such a cathartic experience when you read a piece of work, and you know the other languages. It's like a little secret, right?

You know that a majority of people won't understand what it means, but you understand, so you feel special.

I love giving that feeling of [having] a special connection with certain readers because the story would be more to them than others anyway.

Angela: The Chinese phrases that you used were actual phrases that the protagonist had to learn when she was meeting Mei's family, but your uses of Bahasa were more seamlessly woven into the sentences. How did you choose which words feel right to use in Bahasa, and which ones to keep in English?

Natasha: With the Mandarin, I asked my grandma because both of my grandmas can speak fluent Mandarin. One of them actually wrote a dissertation in full Mandarin when she was sixty. So, I consulted her, and she helped me choose Mei's name and checked all the phrases to make sure they made sense. With the Bahasa, I tried to use words that you can't technically translate into English. I think in every language, there are those really specific words that'll take you a paragraph to explain what it means. So I tried to use those. Otherwise, there are [names of] drinks or food where I don't really want to change it to English because it sounds —

Angela: Wrong?

Natasha: Yeah. It just sounds weird.

Angela: I really, really like that. I did have to scroll up and down to the glossary, but there were instances where I could kind of guess what words meant based on context.

Now, I can't swim and I have a very deep primal fear of deep water (I'm going to blame Finding Nemo). So the idea of cave diving? Absolutely terrifying. However, your protagonist is quite drawn to it and makes a hobby out of it even well into her seventies. Where on the spectrum do you fall?

Natasha: Probably closer to my protagonist. I love the ocean, but I don't think I would do the dive. I don't know why anyone would want to go down there.

It just looks like the end of the world. It's just a black hole.

But yeah, I grew up swimming a lot. I think if you look through my childhood photo album, 50% is me in a body of water, either at the beach, or in the swimming pool with my floaties. Even when my mum was pregnant [with me], she had never been more drawn to swimming. I felt bad for my parents who had to explain that I can't physically ever become a mermaid. Plus, Indo is an island nation, so we have so many beaches.

I do understand where the fear comes from though. Unless they grew up surfing or swimming, it's just not very common for someone to suddenly feel compelled to go into the water at the beach. But I almost never swim now, especially because of COVID. You [couldn’t] even go into pools, let alone beaches, so I understand that sense of fear now. I never used to have it but if there's a long enough gap between the time you go into the ocean or the pool, you rebuild that fear. And it's not the fear of animals for me, it's more like, "What if I can't keep myself afloat?" I did feel that [way] a couple of times when I went back to the beach. It just means I need to be more consistent so I can wash off that fear.

Angela: So when you were doing research into cave diving and into various ocean holes around the world, not for a second did it ever cross your mind, "I'm never going to go in the ocean ever again"?

Natasha: No, I was just like, "How cool! I would want to see it with a boat with a glass floor or something."

You can read Natasha's short story, 'The Blue Hole', in Everything, All At Once (Ultimo Press).

A vibrant and essential collection that celebrates the future of Australian writing, Everything, All At Once showcases showcases 30 emerging writers under 30 as the winners of the inaugural Ultimo Prize. Brimming with a host of intriguing characters seeking comfort and connection in an uncertain world, this collection of short fction and poetry sets the agenda for the next generation of Australian writing.

-

-