As unbelievable as it may sound, I was once taunted by a mouse.

At three in the morning, sometime after Easter, chocolate eggs started rolling under my bedroom door. It started with one. Still sleepy-eyed and unaware, I shoot up from my bed, in disbelief that I could be woken up at this hour. And there lay an egg, still in motion, rolling around on the spot. Thinking I have fallen victim to a silly, childish prank, I get up and storm into my brother’s room.

“What are you doing?!”

The room is dark and there’s a lump hiding under the sheets. That’s some dedication.

“Huh?”

He grumbles and waves me off like he’s just woken up. I’m starting to think that maybe he has.

I’m back in bed, and just as I’ve started to doze off, I hear scratching. Another egg rolls under the door. This time, bits of the wrapping have been nibbled off.

This has to be some sick joke. As I get up to chuck the egg away, I pause, and decide to leave it there.

I’ll use it as bait.

At this point, I’m wide awake. I’m lying down, lights off, and staring at the ceiling. I’m haunted by

this mouse. There might be more. They’re in my walls, watching and waiting, for the moment I fall asleep to scurry out and roam free.

I close my eyes, thinking it’ll heighten my other senses. I hear a slight movement, and I’m up in a second. By now, my eyes have adjusted to the dark and I see a tail dart away from the gap under the door. The egg is gone.

I stuff a towel under the door and pretend to fall asleep until I do.

The Medieval Bestiary: The mouse is born from the soil.

…

Mice are said to be born from the moisture of the earth, the soil, the dirt. They are inherently of dirt, they are dirty. Because of this, they are most commonly associated with disease—the bubonic plague being one of them.

In The Middle Ages, mice were carriers of Yersinia Pestis, a zoonotic bacterium that was responsible for the plague. Despite its fast-acting nature, the bacterium undergoes several stages before the plague can be spread effectively. And, while rodents get the reputation as superspreaders, it really starts with a flea.

Yersinia Pestis is first ingested by a flea, where it finds its way to the digestive tract and multiplies until a blockage occurs. Now infected, the flea bites another host, and its bacilli are regurgitated, spreading through the host’s lymphatic system to the lymph nodes where they produce proteins that disrupt the body’s inflammatory response. By now, the host’s immune system is at an all-time low, and the bacilli know it. They take over the lymph nodes, causing them to swell up and form into buboes. While the bubonic plague was most known for its growth of buboes, other symptoms included: fever, chills, headaches, nausea and vomiting, body aches, and even delirium. If left untreated, the disease can progress to the septicemic stage, infecting the host’s bloodstream. At this stage, the plague kills almost 100 percent of those it infects. Eventually, it turned into a pandemic—known as the Black Death—which devastated Europe from the 14-16th centuries, killing upwards of 25 million people.

Although it seems like mice were to blame for all the death and turmoil that came from the Black Death, most people forget that they, too, were victims of the disease. During these times, mice developed similar symptoms and eventually met the same demise, with rodent populations suffering from high fatality rates.

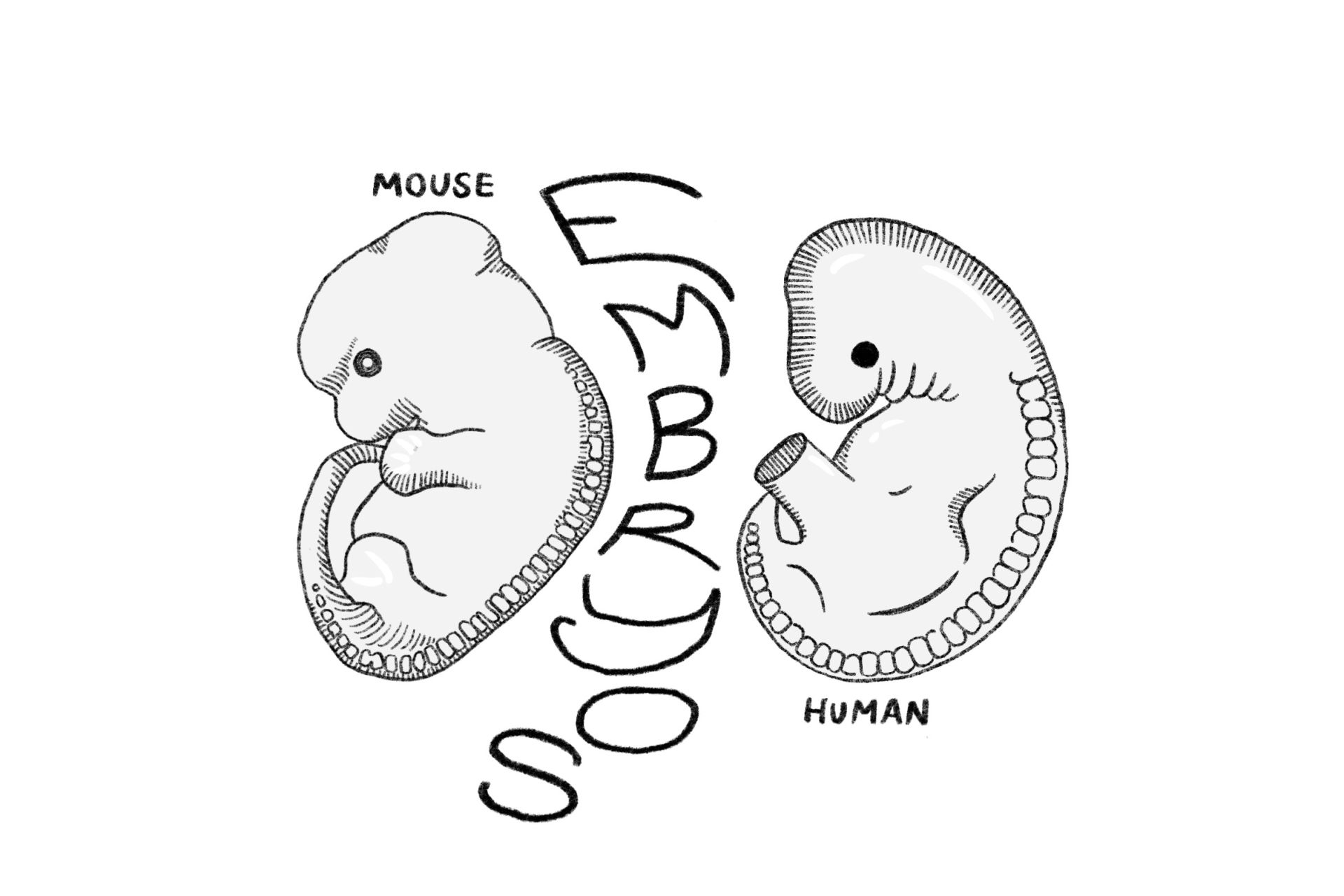

Mice and humans are alike. They form intricate social bonds within their colonies and are known to be incredibly empathetic creatures. Beyond this, mice have about 85% of the genes that code for proteins in the human body, meaning that mice and humans develop in the same way - particulary during the embryotic stage! Mice are also prone to the same types of diseases as humans. It is because of this that they are often chosen as subjects of experimentation.

In 1968, at the National Institute of Mental Health, biologist John B. Calhoun conducted an experiment in which mice were supplied with an unlimited source of food, water, and bedding; they were given everything, except space. The Mortality-Inhibiting Environment for Mice, otherwise known as Mouse Utopia, aimed to understand how social behaviour can change in overcrowded environments. In their habitat, the mice were protected from the threat of predators and exposure to disease. So, they started to breed, continuing until numbers reached a total of 2,200.

At this point, the utopia turned to hell.

With the population at its peak and space at a minimum, the mice began to exhibit abnormal, destructive behaviours. Unable to escape, the juveniles and runts of the habitat became primary targets as males aggressively attempted to assert their dominance within the hierarchy. In their reign of terror, they would regularly attack others of their own volition and forcibly mate with other mice. Sometimes, violence would escalate to the point of cannibalism. Even the alpha males could not withstand the strain of limited space as they struggled to defend their territories from one another. And they soon grew tired. As a result, nests were overtaken, and mothers prematurely kicked out their young in stress. Deprived of guidance, the young failed to develop healthy social bonds, and most died out. The remaining adult mice kept to themselves, hiding away, obsessively and relentlessly grooming themselves. The social structure of the habitat was destroyed, and isolation ensued. Reproduction rates declined, and the population plummeted, failing to recover. By 1973, the population had fallen to zero.

Mouse Utopia was officially over.

…

“What is really catastrophic and where the real fear is, on a level where the mice and man are extremely similar.”

John B. Calhoun, 1972

…

Through Calhoun’s experiments, the concept of a “behavioural sink” was coined to describe the collapse in social behaviours due to overpopulation. In his work, he aimed to prove that social density was just as crucial a factor as physical density.

While Calhoun’s experiments pointed to the grim consequences of a congested future, he did not think humanity was doomed. He rejected the idea that human expansion would always lead to social dysfunction and ecological disaster. Instead, Calhoun thought of population density as a catalyst for innovation and social evolution. He saw humans as “positive animals” whose adaptability and capacity allowed for reimaginations into societies where they could live in healthy and sustainable urban populations.

However, as groundbreaking as Calhoun’s experiments were in the understanding of human behaviour, mice, as always, were reduced to mere subjects of experimentation. Despite being sentient beings, their existence was filled with suffering, and their suffering became an afterthought, overshadowed by the pursuit of scientific progress. They were stripped of complexity and care, and yet it was surprising when the experiment resulted the way it did. When their social structures collapsed, when they turned on one another, and when their population came to an inevitable end.

The experiment awakened something raw and primal in the mice, but they acted like animals because we treated them like animals. And though Calhoun viewed humans differently, if we were subjected to the same environment, I don’t think we’d be any different.

…

I think back to the mouse that taunted me.

The morning after, we bait some catch and release traps with cheese – of course.

Nothing.

“Maybe try a chocolate egg,” my brother suggests.

I laugh but I try it anyway.

The next day when I go to check the trap, the egg is gone. In its place, a mouse scurries around the small, clear enclosure. And I see something alive. Not an experiment, or a metaphor, just a mouse.

Suddenly, I think of the Mouse Utopia. I think of the chaos, violence, and death that raged through the confined habitat. I think of their bodies being tossed away like any other piece of trash. I think of how they couldn’t even find peace, even after death. And in this moment, the separation between human and mouse feels a little more blurred. I think, I wouldn’t wish that on anyone, or anything.

So, I set the mouse free.

-

-