Documenting Dreams and Reminiscing Reality: A Discussion with Gabrielle Menezes

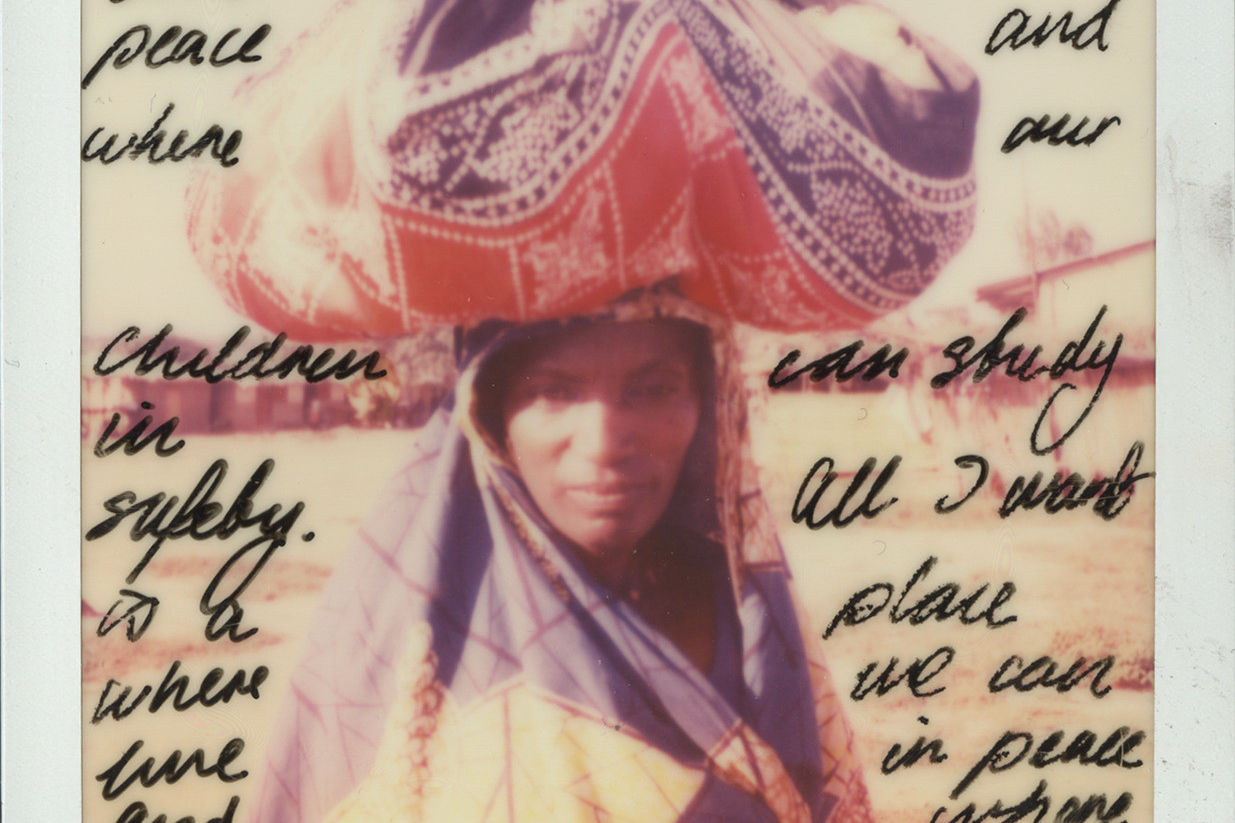

Capturing the dreaminess of memories and the camaraderie of community, Gabrielle Menezes’ photography and multimedia portfolio is a reflection of her passion for emotional connection. With work spanning from UNICEF to Untainted Magazine, Gabrielle's storytelling explores subjects such as the plight of refugees, juvenile justice, Indigenous rights, and folk stories.

Vertigo had the chance to talk with Gabrielle about her experience of working in conflict zones, her photography journey, and her artistic aspirations.

Images provided by Gabrielle Menezes

V: Could you tell our Vertigo readers a bit about yourself.

GM: I have quite a varied background from most people. I grew up in Zimbabwe, and I left at the age of 18. I went to study in London, and then I went to study television journalism in New York. I was doing an internship at Reuters and ended up working at the UN, and a few years later, I became the West Africa correspondent for Al Jazeera.

V: You're a self-taught photographer. What influenced you to pursue photography, and how did you develop your style?

GM: For a few years, I didn’t delve into polaroids or film photography. I was on a very steep learning curve on how to shoot, and I learned a lot in Haiti, where I got a job making documentaries for UNICEF a year after the earthquake. I began exploring how to not just take constant images but create images with feeling. I think this is the difference between good images and bad images; you need to have an emotion provoked in you when you see something.

I started to try out different cameras, and none of them really gelled until an old boyfriend had an SX70, and from the moment I saw it, I just wanted to use those cameras. I loved everything about it. I love the way we take photos with it, I love the look of it, and I love that polaroids are physical objects. What I really love is the element of surprise. I love how there's sometimes something that you never intended to capture, and it's sometimes the best thing about an image. With certain types of polaroids you can really distress them and push the light as far as it can go in comparison to taking images with a digital camera, which are much less interesting because it's like shooting with a big computer — you know exactly what to expect.

V: You have a varied background in documentary and news journalism. How has your journalism career informed your photography?

GM: I think that because I have a background in journalism I was really interested in exploring visual storytelling in a way that wasn't journalistic, and that wasn't just related to the facts we see before us.

For me, there’s much more than the factual truth — there’s an emotional truth, and these aren’t necessarily the same thing. Our reality is made up of dreams and past and present and imagination, and that’s how we filter what we see and experience

In my storytelling, I'm really interested in exploring that, so I think that's where you see this dreaminess coming into my photos. I'm really interested in experimenting when I’m writing on polaroids as to how it can create depth or how you can tell a story that is completely different from the visual story that you're seeing. This gap between reality and our internal emotions is something that I enjoy exploring.

V: You have an impressive photography portfolio, much of which involves work with United Nations agencies. How did you get involved with these agencies?

GM: After I left Al Jazeera, I was asked if I would be interested in doing a consultancy. This was at a time when the world was exploding and there were high food prices in protests worldwide. This was in 2009, so we went to Kenya as they wanted someone who knew Africa and the media very well so they could hit the ground running as a spokesperson organising field visits. I realised there was this huge gap in creating quality multimedia and working with the UN, and that's what I've been trying to fill in my career.

V: You have extensive experience with working in conflict zones alongside refugees. What challenges do you encounter while photographing these projects?

GM: It's always challenging working in a conflict zone or a place where your security is at risk. As a journalist, it's much more dangerous because you don't have this big organisation to rely on, so you create very strong, trusting relationships with your cameraman, with other journalists, and with your producer because they are the people who are going to help you. If you’re working for the UN, you have much more of a support network to rely on.

I think that one of the things that we all deal with is how to process all of these emotions. There is this feeling that I shouldn't be so upset about things because I chose to be there. The reality is that sometimes I am traumatised by being in these places, and I think it’s really important to build emotional resilience and to recognise when you are getting a bit burnt out

V: Tell us about your creative process.

GM: I don't really think that I have a creative process, but I am very inspired by dance, so this was why I did a series in Sri Lanka about devil dances. Devil dances are a type of exorcism dance, and in Sri Lanka, people believe that spirits are the cause of a lot of illnesses. We got a whole bunch of dancers to participate in the project, and we identified new demons that they felt were causing difficulties in Sri Lanken society, such as discrimination and the trauma of war. They each made an exorcism dance to chase away these demons, so I think that was a project where I was very interested in exploring aspects of a certain culture.

I'm also very inspired by light and exploring how far you can push cameras in different lights. Dusk is my favourite time of day. Everything starts to turn blue and time passes so quickly, and that's when I like to get out my cameras and start exploring using different filters. I’m very interested in incorporating different textures into photographs so they can look more like drawings or paintings.

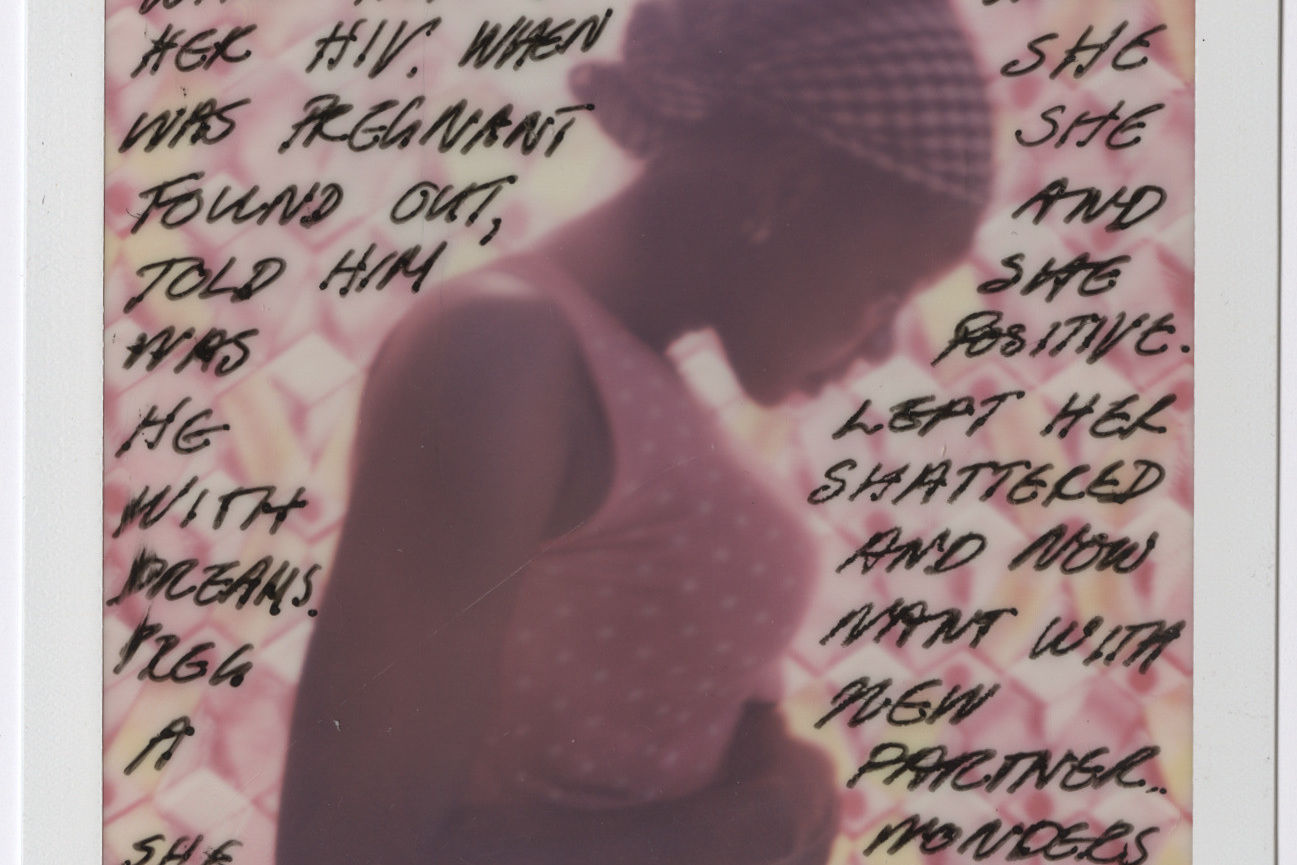

V: I love the blend of documentary and creative images in your HIV in Côte d’Ivoire project. Which style do you prefer, and how do these two modes of photography aid in telling a visual story?

GM: The reason I started doing more art photography was as a reaction to documentary journalism, which has a rigid storytelling format, and I often felt like we were taking something away from the people we were filming and objectifying them. I felt like there were better ways to tell stories.

Fiction, for me, is much more of an active empathy for people; they have to make an imaginative leap and put themselves into someone else’s shoes.

I feel art does that for us, whereas journalism, because it needs to try and remain objective and fact-based, doesn't do the same thing. I think the best journalism tries to do that, but it doesn't transport you in the same way, and I think that this feeling of empathy is what I'm trying to create most — it’s how I want people to experience what I do

V: What are the main principles guiding your photography and multimedia work?

GM: My photography is about exploring what's underneath the reality that we can all see and getting a sense of people's emotions and dreams — how to make the internal external when capturing an image. It's always human stories that I find interesting, and I very rarely take landscape photographs. During COVID-19, it was really difficult because I couldn't photograph people, so I started doing still lifes, especially of flowers. Like so many artists, I'm inspired by their fragility and how something so beautiful dies very quickly; there is that sense of mortality. Even through these still lifes, I was continuing to make up stories and put emotion in them, like some of my fruit photographs looked like broken hearts.

Beyond that, when I do tell stories through my portraits, I show respect and try to tell them with honour for the people sharing these very deep things with me.

V: What project has meant the most to you?

GM: I think all of my creative projects mean something to me. I did a project when I was really getting into the start of working with polaroids called 'Journal of Imperfect Dreams', and that was really special because it was part of processing being a correspondent. Working in conflict, I was trying to explore the disconnect between working in these places and then going home, going to photo festivals, going to parties, and feeling like people didn't understand what I was going through. I felt like I was an alien, and I think this is the project that I tried to express that in, and so it was a very personal project, almost like a diary of memories, dreams, and thoughts that I had.

V: What advice do you have for young artists trying to find their distinct style?

GM: It’s something that you need to explore, but it's also something that happens to you. For me, as soon as I saw polaroid cameras I knew that I wanted to use them and there's something that really spoke to me about the process; how they're not sharp and you don't get a lot of details in them. To a certain extent, I think your style finds you, but I also think that you need to push it in the direction that speaks to you and you need to be fearless when creating work.

If you’re looking for more work by Gabrielle Menezes, you can find her on Instagram @the_instants or check out her website: https://www.gabriellemenezes.com!

-

-