Climate recovery: the road to electrification.

The Wires That Bind is for all the people who have spent the last few decades in a state of climate paralysis, knowing that there is more that can be done but lacking the knowledge of how and where to start.

Replacing our many gadgets as they break has become a default part of modern living. It’s an event that happens every year, or (hopefully) every few years, and is one that is met with annoyance but not resistance. We know our machines will break – our phones, computers, cars, vacuums, cameras, bikes – we buy these items aware that their life span is measured in years. By the time their anxiously anticipated expiry date finally rolls around, we’ve already been tempted by newer, speedier, glossier, higher-tech and – let's face it – better versions, that dupe us into inevitably starting the process all over again.

No matter how thrifty someone claims to be, a flip phone is now a prehistoric relic only to be pulled from the bottom of an old dresser for a Y2K-themed party. The vintage bike you bought on Facebook marketplace is stylish and has a basket for your groceries, but there’s no denying that the latest electric bike would get you to work in a quarter of the time.

The practicality of these new gadgets is irresistible even for the devout anti-materialist. Whether consciously or subconsciously, as humans we are constantly seeking out tools to make our lives easier, to help us build things better, to get us places quicker, to connect us with our friends faster. Replacing our gadgets with the latest model is undeniably the most effective way to do this.

In his 2023 Quarterly Essay The Wires That Bind, entrepreneur and renewable electricity advocate Saul Griffith states that he believes it is this material side to us – our capitalist desire to replace the old with the new, that will solve one of the greatest threats to modern existence. In his essay, Griffith declares climate change and the natural disaster to follow, as caused by nothing more than a “machines problem”.

Griffith believes that the solution to this “machines problem” is actually relatively simple. All we need to do is just keep replacing our broken machines with newer, electrically run, green machines, starting with the ones in our homes.

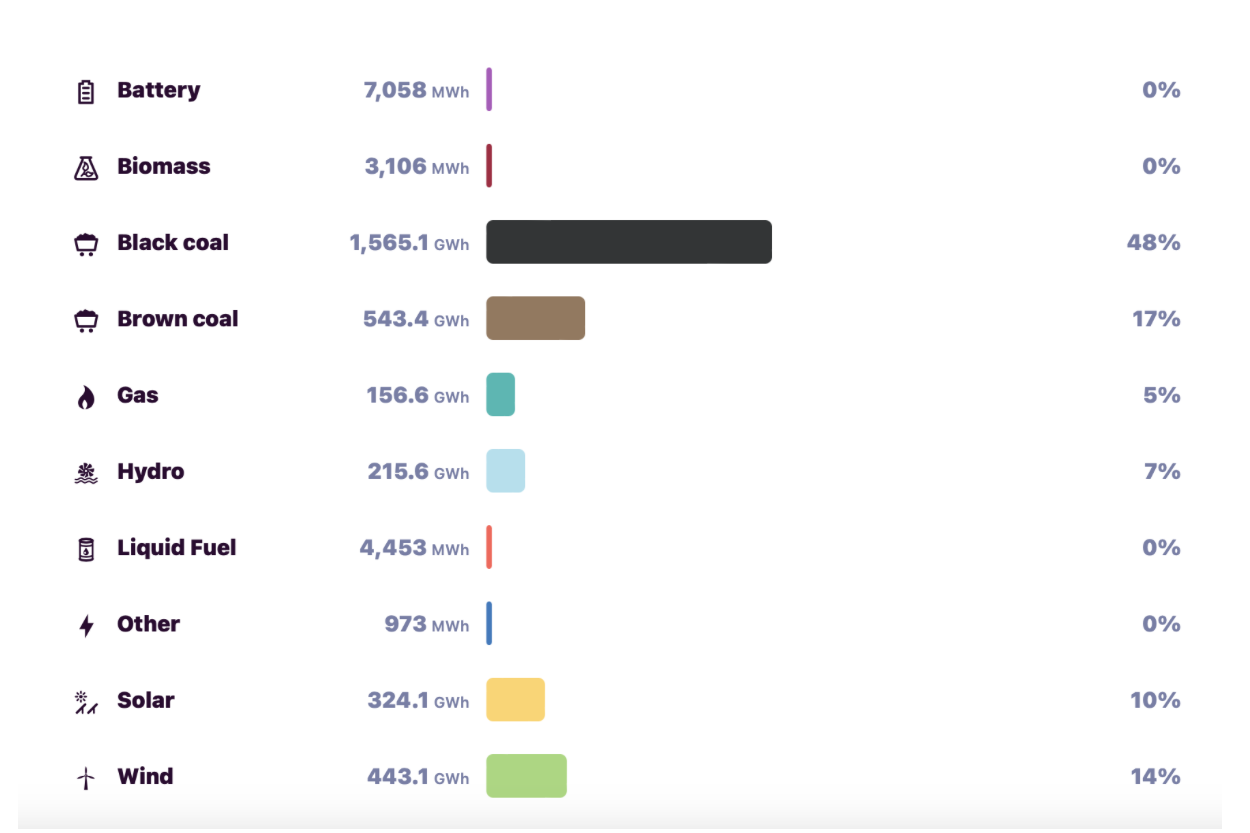

In The Wires that Bind, Griffith acknowledges that running all of our machines on electricity will require a lot of power, and for it to be beneficial, the energy sources driving that power need to be generated in a clean, green way.

The National Energy Market Operator estimates that currently almost half of our annual energy output is powered by coal. However, Australia has the highest per-capita installations globally of Solar PV systems in homes, we have lots of space for renewable energy projects, and we have a legal system that allows laws to be made and enforced promptly. All of these factors combined, gives Australia an advantage over other countries that Griffith believes could allow us to electrify our energy sector completely in a very short space of time. In doing this, Australia could emerge as a leading electric superpower to guide the rest of the world into electrification.

Griffith also hypothesises that this process of transitioning into an electrically run society will happen quite naturally through very simple forces of supply and demand.

To give you an example: as more electric cars are sold, people will need more electric charging stations. Because of this, more will be built and the cost of using them will go down. As more people make this transition and leave their petrol-run cars behind, the cost of buying fuel and the cars that use it will begin to rise, simply because there’s less of them around and they’re harder to run.

In light of this, more tradesmen will be trained to install electronic machines, solar panels and fix electric cars. Finding a fuel service station will become harder, until at some point it will become impractical. This is where the demand curve will flip, and electric machines will become more common than fuel-run alternatives – until the latter cease to exist at all.

This may seem far-fetched, but adoption curves normally have a lifespan of 25 years. It took about 25 years following the creation of cars for them to become the dominant mode of transport. Why? Because driving a car is a whole lot easier than riding around on horseback, and as we’ve learned, humans are constantly looking to make their lives easier.

So, how do we even begin to tackle this machine transition?

Griffith categorises Australia’s machines into two different sectors: there’s the supply side of our machines, which are all the machines that provide us with power. This includes our coal mines, our rail cars, freight trains, locomotives, coal-fired power stations, off-shore gas rigs, terrestrial gas fields, LNG terminals, gas storage facilities and natural gas-fired electricity generators.

Then, there is the demand side of our machines, which are the smaller machines that exist in and around our homes. These include gas and water heaters, ovens, swimming pools, hot tubs, barbecues, oil tankers, cars, trucks, buses, trains, aeroplanes, boats, golf carts, jet skis, lawnmowers, bikes, and everything in between.

Griffith’s research estimates we have about 1 million ‘supply side’ machines, and about 60 million ‘demand side’ machines in Australia, which are all currently being powered by fossil fuels. All of these machines will need to be replaced, and Australia will need to invest money into new infrastructure that will help them function off clean energy. This is where policy and government intervention comes in.

Griffith’s proposal is to slowly transition into electrification through end-of-life policy mandates. In his essay, he states:

“A government could institute a ‘no new gas stove/petrol vehicle/gas heater’ policy after a certain year, say 2025. After 2025, when you went to Harvey Norman or asked a tradie to do the kitchen renovation, the only options available would be clean, zero-emission, electric ones… If all the stoves last fifteen years, it would take fifteen years after that end date of 2025 to get to an almost completely zero-emission fleet of Australian stoves/cars/heaters.”

If the government begins to view all machines, whether on the demand or supply side as infrastructure, and puts in place grants, tax cuts and policies that facilitate their uptake, then Griffith believes we would be able to reduce our emissions to meet international standards before 2050. It also acts as a long term investment, as unlike fuel which is subject to inflation, machinery must only be replaced upon breaking.

“Before you get worried that this transition sounds big and hard – and it is – remember that we have twenty years to get those machines installed. If we just go with the status quo, we will be buying and installing 100 million machines over the next twenty years anyway. (For example, we buy cars at the rate of one million per year, or at least we did before COVID.) So you don’t need to run out and mortgage your house or take out a loan to buy all these electric things in 2023, but rather plan out the pathway for your household to become all-electric by 2025/30/35 or 2040.

When your old Camry or Volvo kicks the bucket, get an electric vehicle. That might be 2024, but it could be 2030. When the water heater goes out, make sure to replace it with a heat pump electric (or even just a resistance electric if it can do demand response). The next time you do a kitchen renovation, select an induction cooktop and electric oven. Replace the gas heaters with reverse-cycle air conditioning and not only decarbonise your winter heat but add cooling for the summer.

We don’t have to switch out all our machines tomorrow. We don’t need to feel guilty about not having ticked off the full kit yet. Because the electrification industry and supply chain isn’t at full scale yet, every time one of these updated electric machines gets purchased and installed, the products get cheaper, the supply chain matures and the machines get better.”

This piece is only a brief summary of a very comprehensive plan formulated by Griffith based on years of research. He is a best-selling author, has worked for twenty years creating leading climate policy in the United States, and is the co-founder of a company called ‘Rewiring Australia,’ who run small-scale electrification projects across the country. Griffith was also nominated for 2024 Australian of the Year.

The Wires That Bind is a call to arms. A piece to inspire radical change starting at the bottom (our homes) and working its way to the top (our government).

One of the biggest problems with the onset of climate change and climate disaster, is that the majority of the public lacks an understanding of what climate change actually is, what the effects of it will be, and how its outcomes correlate with our day-to-day choices. Additionally, climate scientists who understand the science and have formulated the solutions, often fail to present these findings in a way that is palatable for public digestion. These climate conversations are sometimes too dense for the average person, and this perceived lack of understanding has meant that many people have disassociated climate change as being an 'everybody' issue, instead leaving the majority of the work to the professionals.

The power of Griffith’s piece is in its ability to communicate what each individual’s role is in our journey to electrification. The Wires That Bind is for all the people who have spent the last few decades in a state of climate paralysis, knowing that there is more that can be done but lacking the knowledge of how and where to start. It is an answer for those who have carried a keep cup around for years, taken Fridays off school to protest, have attended their local Stop Adani meetings and are still left thinking surely there’s more that I can be doing.

Griffith confirms that there is more we can be doing. This movement is riding on grassroots action, and it starts with the individual in their home.

Griffith’s full essay The Wires That Bind can be found here.

-

-